|

| Image Courtesy of History 365 |

Hell On Earth: Understanding the Congo

Part 2: Bloodshed

Part 1:

Independence

After the Congo had been under a brutal colonization by Belgium, it finally seemed that their independence was at hand. However, there were a number of hiderances which created the Congo Crisis, a situation that had the characteristics of a secessionist war, a proxy war between the United States and the Soviet Union, and a UN peacekeeping operation with the backdrop being the fight for Congolese independence.

Military Mutiny

It must first be noted that in the Congo, the military had only whites in command positions, even though there were “three African sergeant-majors in an army of 24,000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers, 542 officers, and 566 junior officers.” This was because due to a limited education, few Congolese officers had the proper experience to lead the military and thus the European officers needed to be retained. Even nationalist Patrice Lumumba “felt the need for continuity in the army-that is to say, for the retention of European officers” and stated as such to the Congo Executive College two months before the Congo became independent. Specifically, he stated that the military must stay “exactly as it is-with its officer class, its junior officers, its traditions, its discipline, its unique hierarchy and above all its morale unshaken."[1]

With the average soldiers realizing that they would remain in the same situation of obedience, rather than having opportunities for advancement, they rose up in a rage, seeking not only increased authority, but also an increase in pay. The mutiny began at the Thysville military base and quickly spread across the country. Once the mutiny had started, “stories of atrocities against whites surfaced in newspapers around the globe” and due to the fact that mainly Belgians were fleeing the Congo, the Belgian government brought in troops to restore order[2], even though Lumumba had denied a request from the Belgians to do so. This violated the friendship treaty between the two nations which stated that Belgian troops “may be used on Congolese national territory only upon the specific request of the Government of the Republic of the Congo, in particular, on the specific request of the Congolese Minister of Defense.”[3] It was around this time that the situation became even more unstable with the secession of the Katanga region.

Katanga Secession

As has been noted beforehand, the Katanga was quite an important part of real estate in the Congo due its large mineral wealth. Yet, there were much greater problems than just natural wealth at play.

Economically speaking, while the Katanga region did have a large amount of mineral wealth, the capital was held in the hands of one company: the Union Miniere du Haut Katanga (translated as Mining Union of Upper Katanga, UMHK). Having immense economic resources that are controlled by one company would have serious political implications both generally but especially for secession, namely, that Belgian aid was needed as the region was so dependent on Belgian technicians and investments.[4] Some sectors of the Katangan population viewed the province as “’ the cow that the other territories never tired of milking.’”[5]

The economic status of the province played into the ethnic tensions of the population. Industrialization of the Congo was mainly within the southern region of the province, where the three major mining centers were located, creating a rather large amount of uneven regional development. This was reflected in the uneven distribution “of social overhead capital-commercial centers, communication facilities, schools, hospitals, etc.”[6] This uneven development created ethnic tensions as the UMHK received much of its labor from neighboring Kaisai province. For example, the Luba of Kaisai, even though they were ethnically related to the Luba people of the Katanga, formed their own unique culture and this presence of ‘aliens’ helped to make both groups more conscious of their differences.

Besides the ethnic tensions between Congolese, another factor was the presence of Belgian settlers who had their own agenda. The interests of the settlers lined up with those of the economic elite as the settlers formed the Special Committee of Katanga, “whose principal function was to promote, in every possible way, the development of an agricultural colony. To serve this purpose, a [Frontier Syndicate of Katanga] had been set up in 1920, thanks to the financial backing of the UMHK, [the Congo Company for Trade and Industry] and several other large-scale capitalist enterprises.” In addition to this, besides the corporate interests, the settlers themselves had personal political and economic interests as they desired the special administrative status with a Vice Governor General, which acted as a representative of the Belgian monarchy.

Economically, they felt that “the proportion of public expenditures devoted to the Katanga appeared minute when compared with the over-all contribution of its taxpayers to colonial revenues.”[7] Thus, through a combination of ethnic tensions and economic interests, when the province finally decided to secede, it was “supported by a Belgian mining company and was backed by Belgian troops almost from the very beginning.”[8] Moïse Tshombé, a pro-Western anticommunist, was elected to lead the breakaway province and Katanga officially seceded on July 11, 1960. It was due to this secession and the Belgian intervention due to the military mutiny that Patrice Lumumba appealed to the UN to intervene.

Both Premier Patrice Lumumba and President Kasavubu went to the UN Security Council to plead their case for military intervention, with the goal of “[protecting] the national territory of the Congo against the present external aggression which is a threat to world peace.” They also alleged that “the Belgian Government of having carefully prepare the secession of the Katanga with a view of maintaining”[9] a hold on the Congo. The Council voted in favor of intervention, with there being only three abstentions of China, France, and the United Kingdom out of concern for Belgian interests.

From there, “contingents of a United Nations Force, provided by a number of countries including Asian and African States began to arrive in the Congo” and “United Nations civilian experts were rushed to the Congo to help ensure the continued operations of essential public services.”[10] The UN force would remain in the country for the next three years. However, it is rather interesting that both the USSR and the US would even agree on something like this, thus it is time to explore each of their respective interests in the Congo.

Foreign Interests

On a regional level, the US and Soviet Union both viewed Africa as important as “The question of independence for the colonies was championed by the USSR,” while the US and its allies can up with ways to “either delay the granting of independence and/or to involve the newly independent countries in their [the West's] global anti-communist crusade.” Demands for freedom by colonized populations were viewed as “a communist inspired movement, thus implicitly suggesting that the colonized peoples preferred to remain colonized.”[11]

The focus on independence allowed for the Soviets to gain a foothold in Africa as it could be seen as wanting equality and independence for oppressed peoples around the globe. The Soviets viewed the liberation movements sweeping Africa and Asia as “damaging to the West and therefore beneficial to World Communism—if it could be properly exploited.”[12] Thus, their goal in Africa was to aid the expansion of Communism. When Lumumba turned to the Soviet Union in August 1960 for aid to battle the Katanga secession after the UN refused to intervene[13], he was immediately seen as a Communist sympathizer or a useful fool for the Soviets in the eyes of the West, though it aided the Soviets in expanding their influence and building a reputation as supporting independence for oppressed peoples. While this would come back to haunt him, for the Soviets, it worked quite well to boost their credibility in the eyes of countries fighting colonialism.

The United States had a number of interests in the Congo. From the very start the West had been hostile to Lumumba as they saw him as over-nationalistic and an unreliable ally in the East-West conflict. When he accepted aid from the Soviet Union, this view only intensified. The US also had a number of economic interests in the region as well, with there being a number of high-level connections to corporations and the US State Department and other organizations.

For example, the Liberian-American Mineral Company was led by “Bo Gustav Hammarskjöld, brother of the U.N. Secretary General” and “Under-Secretary of State George Ball, who was directly in charge of making U.S. policy in the Congo,”[14] was a former member of Fowler Hamilton’s law firm, which represented the International African American Corporation, a UN mineral syndicate in the Congo. The aforementioned Mining Union of Upper Katanga had stock held in it by “American companies like Lazard Freres, the New York investment house” and “Allan A. Ryan, an American, [who] was director of the Belgium-American Banking Corporation” held 25% of the shares in Mining Union and “the Rockefeller Brothers [held] less than 1% of [Mining Union] shares.”[15] While Howard Kersher, a newspaper reporter, did not find a smoking gun linking these people to the problems in the Congo, it was quite obvious that they all had financial interest in the Congo and thus a stake in what was going on in regards to the Katanga secession.

From a geostrategic perspective, the Congo was important to the US as Congo could have a serious influence upon its neighbors, Cameroon, Gabon, the Central African Republic, and Sudan. US officials were worried that if a pro-Communist government came to power, it could set the tone that other African nations would follow and on a larger level, aid the Soviet Union in spreading Communist ideology. The Congo was valuable from a military perspective in that a key front in WW3 would be the Middle East and they assumed that Soviets would attempt to block routes to that theater and “Soviet generals and planners would understand the importance of the Mediterranean Sea, the Suez Canal and even the waters surrounding the coasts of South Africa” to overall US strategy and that “any Soviet attack would make security of these routes integral to its plan.”[16]

Overall, the US “detested Lumumba and were determined to overthrow him, and this became the principal objective of US policy during the first six months of the Congo Crisis.”[17] CIA Director Allen Dulles warned of a “communist takeover of the Congo with disastrous consequences ... for the interests of the free world” and “authorized a crash-program fund of up to $100,000 to replace the existing government of Patrice Lumumba with a ‘pro-western group.’”[18] While the superpowers did have their respective interests in the Congo, the situation would intensify with the secession of South Kasai.

South Kasai

The South Kasai region, like the Katanga region, was rich with mineral wealth, mainly diamonds. Until the mid-1970s, it produced one-third of global output of industrial diamonds. Though mineral wealth was important due to the economics of the Congo, it was mainly ideological differences and ethnic conflict that caused the secession.

Ideologically, the secession was led by Albert Kalonji, who had been prominent figure in the Congolese National Movement party, but later split off from Lumumba to help form a more moderate wing of the nationalist party, which came to be known as MNC-Kalonji. Like the Abako political party, the Kalonji wing of the MNC preferred a centralized system in favor of autonomous provinces based on ethnic lines.

With regards to ethnicity, the secession “can be traced to the territorial expansion of the Baluba beyond southern Kasai to the Lulua area in the late-nineteenth century, which created animosities between the Baluba and the Lulua.”[19] This territorial expansion of Baluba peoples due to lack of cultivable land saw the Baluba move permanently into the region and attain most of the clerical colonial jobs. “The fear of domination by the Baluba prompted the creation of the Association of Lulua-Frères in 1951 by a Lulua chief, Sylvain Mangole Kalamba.”[20] Tensions eventually reached a crisis when “the local administration proposed to resettle Baluba farmers from Lulua land (an economically booming center province) back to their impoverished homeland in southern Kasai.”[21] Kalonji exploited these ethnic tensions for political gain and declared secession of South Kasai.

The Rise of Mobutu

While the country was wracked with political turmoil, it provided the perfect atmosphere for a coup. On September 6, 1960, President Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba and appointed Joseph Ileo as the new Premier. However, his reign was not to last as the Army Chief of Staff, Joseph Mobutu, would soon take power in a coup with foreign help

.

Mobutu already had ties with the CIA that dated back to “his role in the pre-independence negotiations in Brussels where he both reported to the Belgian Sûreté and made his first contacts with Lawrence Devlin,”[22] the CIA station chief in the Congo. These ties only grew during the Congo Crisis when the US and other Western powers funded Mobutu, who, in turn “distributed large amounts of money to the officers and men under his command; through this arrangement he was able to establish bonds of loyalty among his soldiers.” It also didn’t hurt that his unit “was virtually the only really functioning element of the Congolese National Army.”[23] The US aided Mobutu’s rise to power as, has previously been mentioned, they viewed Lumumba as a Communist sympathizer and they needed to get rid of him in order to ensure that the Soviets would not gain a sphere of influence in Africa.

The first time Mobutu took power was regarding a constitutional dispute. Kasavubu had dismissed Lumumba. Though, both the US and the UN had influence on this action. Andrew W. Cordier, a UN official, and Dag Hammarskjöld, the UN Secretary-General, “coordinated their activities with the State Department” overall and Cordier for September 6, “arranged for UN troops to close the airport -- to preclude any airlift of loyal troops to the capital by Lumumba” and then “ordered UN forces to close the radio station as well, which prevented Lumumba from broadcasting an appeal for support.”[24] This encouraged Kasavubu to act against Lumumba, however his plan would backfire as Lumumba would receive full vote of confidence from the Congolese Parliament whereas Kasavubu’s appointment, Joseph Ileo, would not.

Due to this situation, the US became even more focused on getting Mobutu into power and advocated for a military coup. On September 14, Mobutu removed Lumumba from office, dissolved Parliament, but quickly “turned the government over to a College of Commissioners composed of the few college graduates the country possessed.”[25] He placed Lumumba under house arrest, but Lumumba was soon freed by loyal Congolese troops. Mobutu then again captured Lumumba and placed him under house arrest with a UN guard.

Upon hearing that Lumumba had been place under house arrest, Vice Prime Minister Antoine Gizenga set up a rival government in the eastern city of Stanleyville with the help of pro-Lumumba forces. On December 12, 1960, Gizenga declared the nation of Stanleyville, with its capital of Oriental City, to be the only legitimate government of the Congo.

Gizenga quickly turned to the Soviet Union for aid. In a telegram, he asked the Soviets to “immediately, without delay, to help us in military equipment and foodstuffs’ in order to repel the invasion of Mobutu’s troops ‘who unleashed the civil war against soldiers and units loyal to the legitimate government.”[26] Factoring in that they had attempted to aid the Lumumba government and failed, the Soviets took their time in replying to Gizenga. When they did respond, they sent $500,000 in aid as due to the blockade on Stanleyville, they could not transport aid directly to the fledging government and due to infighting among the USSR and its regional allies, and little else was done.

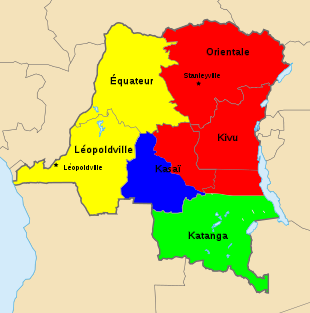

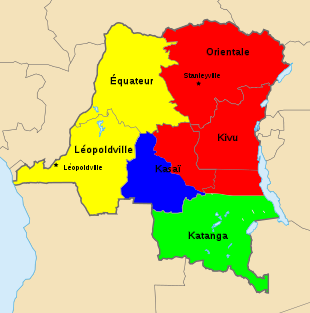

The situation was then where there were four competing governments in the Congo: Joseph Mobutu and Joseph Kasavubu in Léopoldville, supported by Western governments, Antoine Gizenga in Stanleyville, Albert Kalonji in South Kasai, and Moise Tshombe in Katanga.

The Assassination of Patrice Lumumba

As has been previously mentioned, the West had never been particularly fond of Lumumba, especially after he sought aid from the Soviet Union. His assassination came as a surprise to many, but it had already been planned from the very beginning as the US was determined to get him out of the picture, as were the Belgians.

With regards to the assassination, on November 27, 1960, Lumumba left UN custody to make a break for Stanleyville and join his supporters there. However, he was captured by Mobutu’s forces only days later and imprisoned him. In early January 1961, forces loyal to Lumumba invaded “northern Katanga to support a revolt of Baluba tribesmen against the Tshobme government.” Due to ‘security’ reasons, “the CIA and Mobutu decided to transfer Lumumba from Leopoldville to Katanga,”[27] where he and two aides were subsequently killed.

The United States had plans to eliminate Lumumba that went as high as the President himself. In August 25, 1960, a subcommittee of the National Security Council, known as the Special Group, met; Thomas Parrott, the secretary of the Group, began the meeting by outlining the CIA operations that had been undertaken in ‘mounting an anti- Lumumba campaign in the Congo,’ with the meeting ending with the group “not necessarily rule out of any particular kind of activity which might contribute to getting rid of Lumumba.”[28] The very next month, CIA Station Officer Victor Hedgman received a cable from Bronson Tweedy, the Deputy Director of the CIA, in which “he advised [Hedgman], or [his] instructions were, to eliminate Lumumba” and that the orders came from the President himself.[29]

While a Senate report did that there was “no evidentiary basis for concluding that the CIA conspired in this plan or was connected to the events in Katanga that resulted in Lumumba's death,” some doubt still remains as the CIA did have a plan to poison Lumumba and possessed “advance knowledge of the central government's plan to transport Lumumba into the hands of his bitterest enemies, where he was likely to be killed.”[30] The US government, at the very least, played a role in the killing of Lumumba.

The Belgians also had wanted to kill Lumumba and were somewhat involved with his assassination. Specifically, they were involved in “weapon deliveries; supporting the arrest of Lumumba; action 58316, (the outline of which is unclear but within which an attack on Lumumba could be relevant); and the kidnapping of Lumumba.”[31] They also had information that the leader’s life was in danger due to being in the Katanga, but the Belgian government did not take any action to protect him; in fact, when Lumumba was executed, it was in the presence of “a Belgian police commissioner and three Belgian officers who were under the authority, leadership and supervision of the Katangan authorities.”[32]

With Lumumba dead, it was only a matter of time before the Congo would be reunited under the rule of Mobutu.

The Fall of the Revolution

During late 1960 and early 1961, it became obvious to the Western powers that “the provisional government of Kasavubu would not last without reconciliation with Katanga, and the U.S. pressed for a federated Congo government which would include Katanga.”[33] The US pushed for the UN Security Council to pass a resolution demanding an end to the Katanga secession. This was passed in the form of UNSC Resolution 161, which stated in part that the UN should “take immediately all appropriate measures to prevent the occurrence of civil war in the Congo.”[34]

However, this was undermined by Belgium and other involved American interests, which didn’t want the secession to end. Thus, they formed an organization called ‘The Committee to Aid Katanga Freedom Fighters,” which allowed Tshombe to “build an army which could resist the UN, financed by Belgium,” yet this armed force also had reactionary forces within it from a number of places. They came from “the United States (Cuban exiles), Britain, France (ex-Foreign Legionnaires), West Germany (ex-SS men), South Africa (fascists), Rhodesia--and, of course, Belgium.”[35]

In February 1961, Kasavubu put an end to the Mobutu reign and appointed Joseph Ileo and Cyrille Adoula heads of the new government, with him remaining as president.. The very next month, Gizenga attempted to make peace with the Congo, but he was arrested by Kasavubu and imprisoned, while Tshombe was forced into exile. Three years later, in 1964, the UN left the Congo Tshombe came back to rule the Congo. During his leave of absence, Tshombe “conferred in Brussels with Foreign Minister Paul-Henri Spaak and the U.S. Ambassador,”[36] which allowed him to return to the Congo and replace Adoula as Prime Minister. Yet, this government would not last. Mobutu would take power in November 1965, once again with the aid of the CIA.

The US became worried in 1964 regarding the competition between Tshombe and Kasavubu, both of whom hoped to rule the Congo after the civil war ended. This concern heightened when Kasavubu “sought ‘an opening to the left’ by dismissing Tshombe and appointing a government ready to consider not only the dismissal of mercenaries, but also the recognition of Communist China and improved relations with left-nationalist African states”[37] and the CIA backed Mobutu as to ensure that no leftist groups gained power.

However, there was also internal politicking as well. The coup itself was a collective decision by senior officers of the Congolese military. They backed Mobutu as “they believed that the army was above partisan politics and their immediate demand after the coup was an increase in the fighting power of the army.”[38] In order to satisfy the military, Mobutu would increase the size of the military and enhance is prestige. Yet, while it seems that Mobutu had finally become the ruler of the Congo, there were internal struggles that he would have to deal with.

Endnotes

1: Claude E. Welch, “Soldier and State in Africa,” The Journal of Modern African Studies 5:3 (1967), pgs 307-308

2: US Department of State, Office of the Historian, the Congo, Decolonization, and the Cold War, 1960–1965, https://history.state.gov/milestones/1961-1968/congo-decolonization

3: Africa Today Associates, “Conflict in the Congo,” Africa Today 7:5 (1960), pg 8

4: Rene Lemarchand, “The Limits of Self-Determination: The Case of the Katanga,” American Political Science Review 56:2 (1962), pg 405

5: Lemarchand, pg 406

6: Ibid

7: Lemarchand, pg 409

8: M. Rafiqul Islam, “Secessionist Self-Determination: Some Lessons from Katanga, Biafra, and Bangladesh,” Journal of Peace Research 22:3 (1985), pg 213

9: Joseph Kasavubu, Patrice Lumumba, UN Security Council Resolution S/4382, United Nations Security Council, http://www.un.org/en/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=S/4382 (July 13, 1960)

10: United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations, Republic of the Congo- ONUC Background, http://www.un.org/Depts/DPKO/Missions/onucB.htm

11: Natuf, pg 355

12: William G. Thom, “Trends in Soviet Support for African Liberation." Air University Review 25 (1974), pg 36

13: BBC, The Congolese Civil War, 1960-1964, http://news.bbc.co.uk/dna/place-lancashire/plain/A1304803

14: Kiama Mutahi, “The United States, The Congo, and the Mineral Crisis of 1960-64: The Triple Entente of Economic Interest,” Electronic Thesis or Dissertation. Miami University, 2013. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/, pg 33

15: Mutahi, pg 32

16: Davis, Erik M., "The United States and the Congo, 1960-1965: Containment,

Minerals, and Strategic Location" (2013). Theses and Dissertations--History. Paper 8. http://uknowledge.uky.edu/history_etds/8, pg 578

17: David N. Gibbs, “Secrecy and International Relations,” Journal of Peace Research 32:2 (1995), pg 220

18: William Blum, Killing Hope: US Military and CIA Interventions Since WW2 (London, United Kingdom: Zed Books, 2003), pg 156

19: Emizet Kisangani and Léonce Ndikumana, "The Economics of Civil War: The Case of the Democratic Republic of Congo," Political Economy Research Institute Working Papers 47 (2003), pg 8

20: Ibid, pg 9

21: Ibid

22: Götz Bechtolsheimer "Breakfast with Mobutu: Congo, the United States and the Cold War, 1964-1981," PhD Diss., The London School of Economics and Political Science (2012), pg 64

23: Gibbs, pg 220

24: Gibbs, pg 221

25: Michael G. Schatzberg , “Beyond Mobutu: Kabila and the Congo ,” Journal of Democracy 8:4 (1997), pg 72

26: Sergei Mazov, “Soviet Aid to the Gizenga Government in the Former Belgian Congo (1960–61) as Reflected in Russian Archives,” Cold War History 7:3 (2007), pg 429

27: Tom Cooper, “Congo, Part 1: 1960-1963,” Air Combat Information Group, September 2, 2003 (http://www.acig.org/artman/publish/article_182.shtml)

28: U.S. Congress, Senate, Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations With Respect to Intelligence Activities, Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, 1975, 94th Congress, 1st Session, November 20, 1975 (Washington D.C.: GOP 1975), pg 60

29:: Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, pgs 24, 26

30: Alleged Assassination Plots Involving Foreign Leaders, pg 48

31: Belgian House of Representatives, Parliamentary Inquiry on the Circumstances of the Assassination of Patrice

Lumumba and on the Possible Involvement of Belgian Politicians, Report of the Commission of Inquiry http://www.dekamer.be/commissions/LMB/indexN.html, pg 6

32: http://www.dekamer.be/commissions/LMB/indexN.html, pg 8

33: Dick Roberts, “Patrice Lumumba and the Revolution in the Congo,” The Militant, http://www.themilitant.com/2001/6528/652850.html (July 23, 2001)

34: United Nations Security Council, UN Security Council Resolution S/4741, http://daccess-dds-ny.un.org/doc/RESOLUTION/GEN/NR0/171/68/IMG/NR017168.pdf?OpenElement (February 21, 1961)

35: Roberts, July 23, 2001

36: Ibid

37: Stephen R. Weissman, “CIA Covert Action in Zaire and Angola: Patterns and Consequences,” Political Science Quarterly 94:2 (1979), pg 273

38: Kisangani N. F. Emizet, “Explaining The Rise And Fall of Military Regimes: Civil-Military Relations in the Congo,” Armed Forces & Society 26:2 (2000), pg 211